How Do We Know? - Part 1: Ways of Knowing

In recent years, a philosophical debate has surrounded my interests in literature and politics. I am increasingly preoccupied with this question: How do we know what we know? The theory of knowledge, known as epistemology, has its roots in the Greek epistēmē ‘knowledge’ and logos ‘reason’. Where reason implies rationality, this leads to a more important question: To what extent is our knowledge justified?

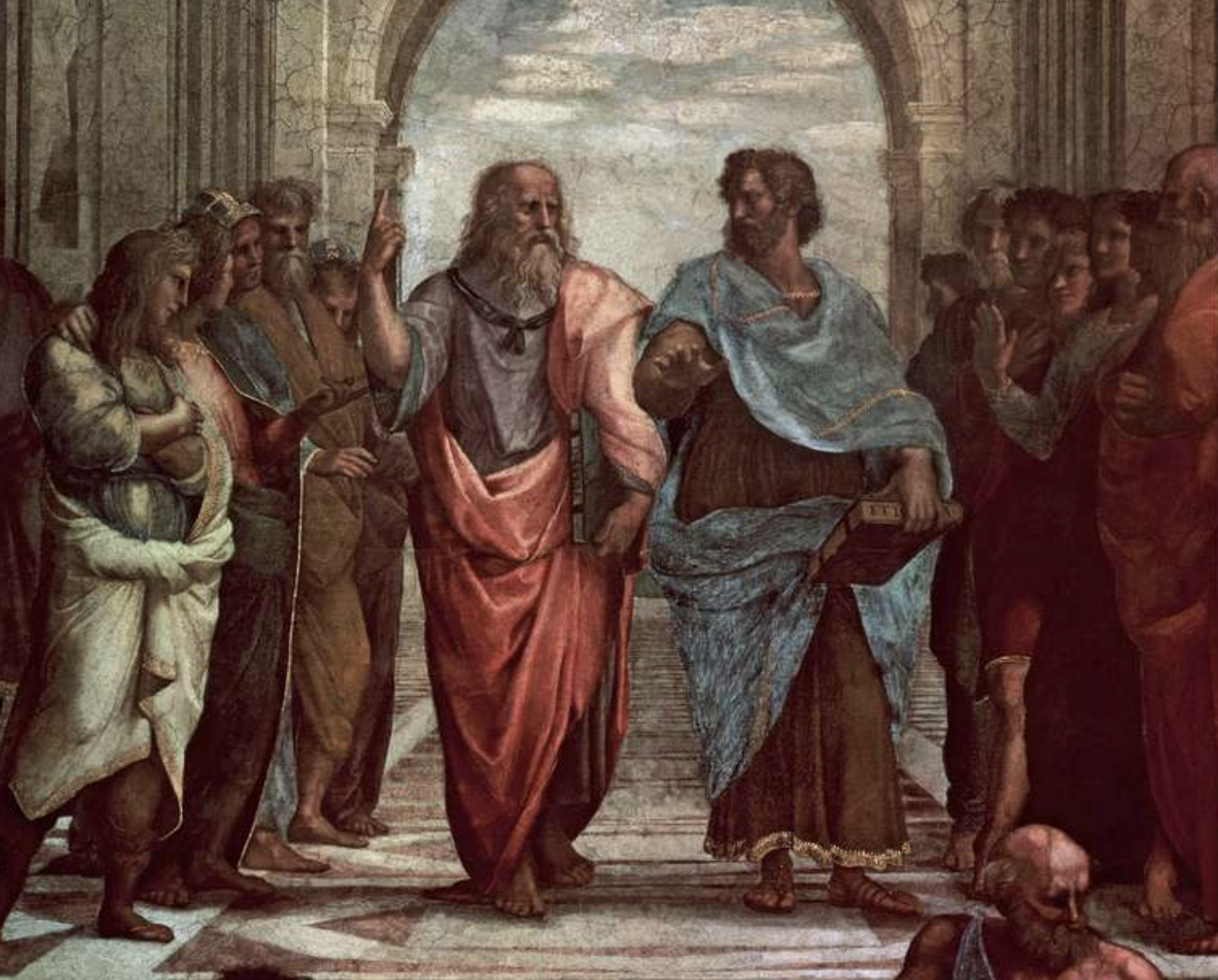

Plato (c. 428–c. 348 BCE) and Aristotle (384–322 BCE) debated this question, with Plato believing in forms existing beyond human perception (Platonic realism), and Aristotle seeking truth in his experience of the natural world. Since the Enlightenment - and Descartes’ 1637 assertion, cogito ergo sum (‘I think, therefore I am’) - the ‘how do we know’ debate has waged between two main schools of thought: rationalism and empiricism. Rationalism contends that knowledge proceeds from deductive reasoning (a priori, ‘from what is before’, meaning logic and objects known), while empiricism argues that knowledge proceeds from observations or experiences to the deduction of probable causes (a posteriori, ‘from what comes after’, meaning after experience). Rationalism favours reason, while empiricism favours sensory perception.

So why does this matter?

You might naturally ask why anyone should care about this philosophical debate. These ideas are abstract and seemingly irrelevant to how we live our daily lives. You know how to cook and drive; you know where the stores are and what things cost. You know how to do your job and take care of your family. You know what you know because you just do, and you get by just fine.

The problem comes when knowledge enters the realm of beliefs and assumptions, particularly when dealing with people and society. You might know, for instance, that you trust someone - believing them to be a decent person. In this way, you assume they are trustworthy. These kinds of character judgments can extend to politicians, determining our support for them. Another example is our tendency to think we know what will happen in various situations; in our speculations, we trust our intuition and instincts, perhaps based in part on facts or data, perhaps on other experiences of life and the world. These assumptions might extend to how elections will go, as those processes are seen to reflect public concerns on current issues.

What is at stake in the question of ‘how we know’ is what’s called rational belief - how reliable our knowledge is, and to what extent our knowledge reflects objective truth.

I will be exploring these ideas as they relate to media and politics in our digital age. Our world is changing rapidly, with recent history bespeaking the hugely consequential - and largely unforeseen - events of Brexit and the rise of Donald Trump, the impacts of which continue to reverberate in society and culture. It is crucial to examine what has happened - and how it has happened - to gain a clear sense of how to navigate and legislate for a world increasingly driven and disrupted by digital knowledge.

Next Instalment: How Do We Know? - Part 2: Bias